Let's learn about the miniature paintings from Mewar!

Introduction

Etymology: Since the Mewar school of painting has its roots in the Mewar province, it is named after its place of origin.

Origin: Mewar school stems from Mewar in the state of Rajasthan.

Location: The important centres for these miniatures are Chittor, Udaipur, and Nathdwara.

Community: The Mewars speak the local language of Mewari and find happiness in a very structured community. They believe in the joint family system and they follow various traditions and celebrations of the Rajasthani culture.

Relevance: In the 19th century European influence was also seen in the paintings of Mewar but typically Kutch mounted prints, this influence changed the whole dynamic of Rajasthani paintings and its schools.

History

Historical background: These miniatures are influenced by the aesthetics of Rajput rulers more than the Mughal rulers as the Rajputs took over the settlement of tribes such as Bhil and Mina. The attire in which the characters are seen in these miniatures is wholly Rajput-Rajasthani clothing.

Culture and societies: Mewar being a district in Rajasthan, is mainly Rajasthani culture. The Mewari dialect is spoken locally, and the Mewars are socially integrated people who enjoy festivals and celebrate the Rajasthani culture widely.

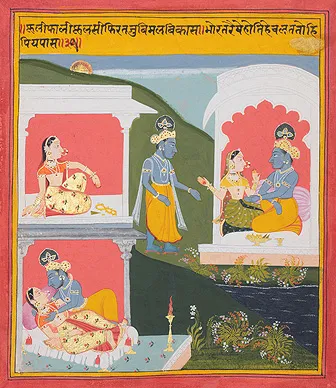

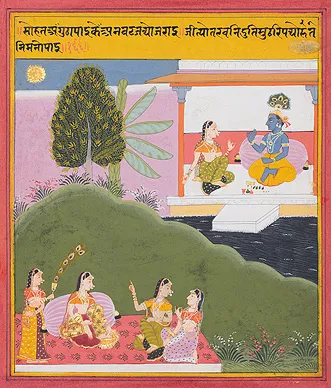

Legends or myths: The mythology of Lord Krishna and Radha is the central theme of these paintings. Romanticism, courtship, and bold display of intimacy were illustrated based on the poetry of Rasikapriya, which mostly talked about the leela between Krishna and Radha.

Understanding the art

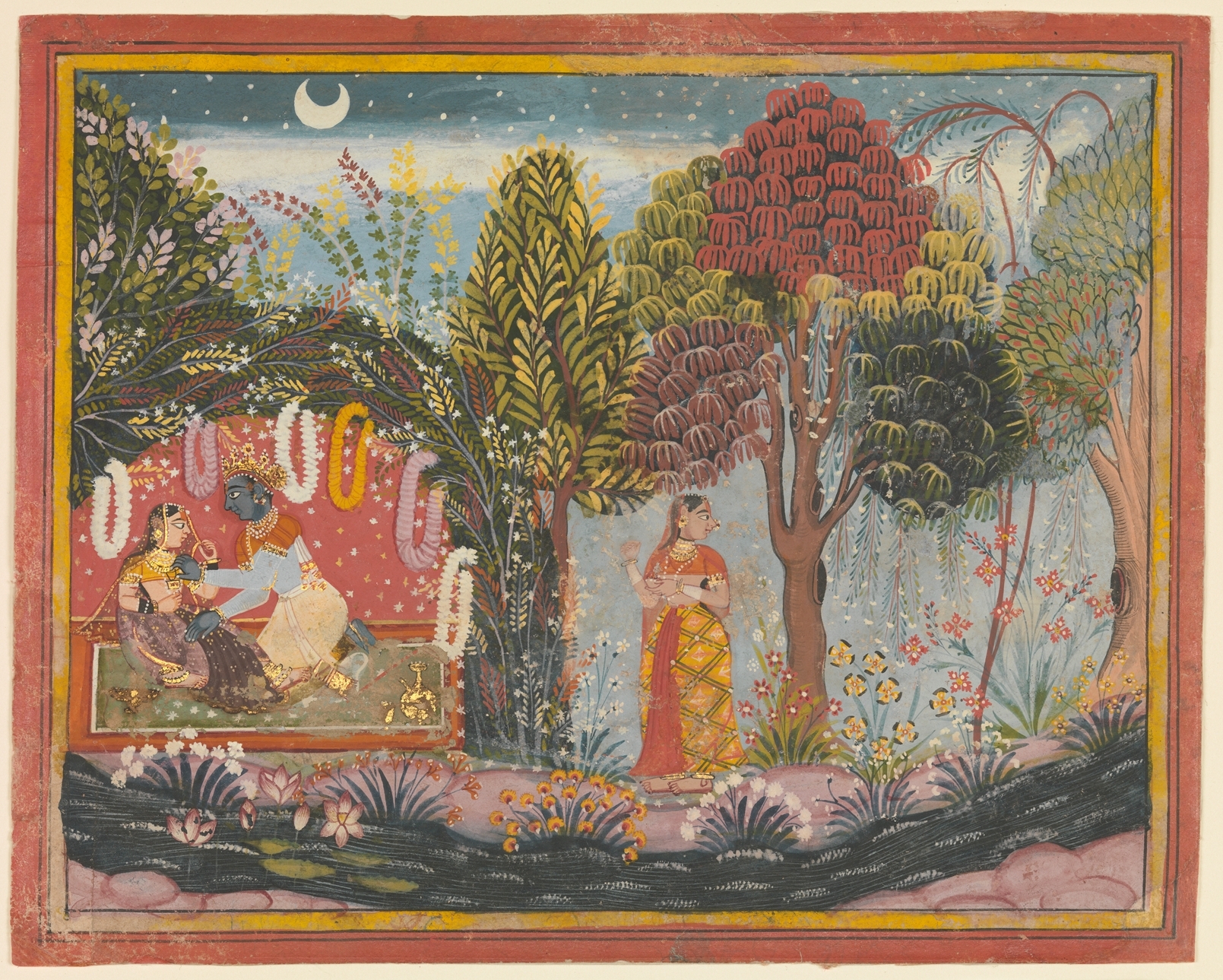

Central motifs and their significance: These paintings depict nature in abundance as the region of Mewar is surrounded by shrubbery, water bodies, and mountains. Mentions of the lotus flower are significant as it symbolizes divinity and purity. Verdant scenery with the scarce depiction of architecture makes the composition of these paintings complete.

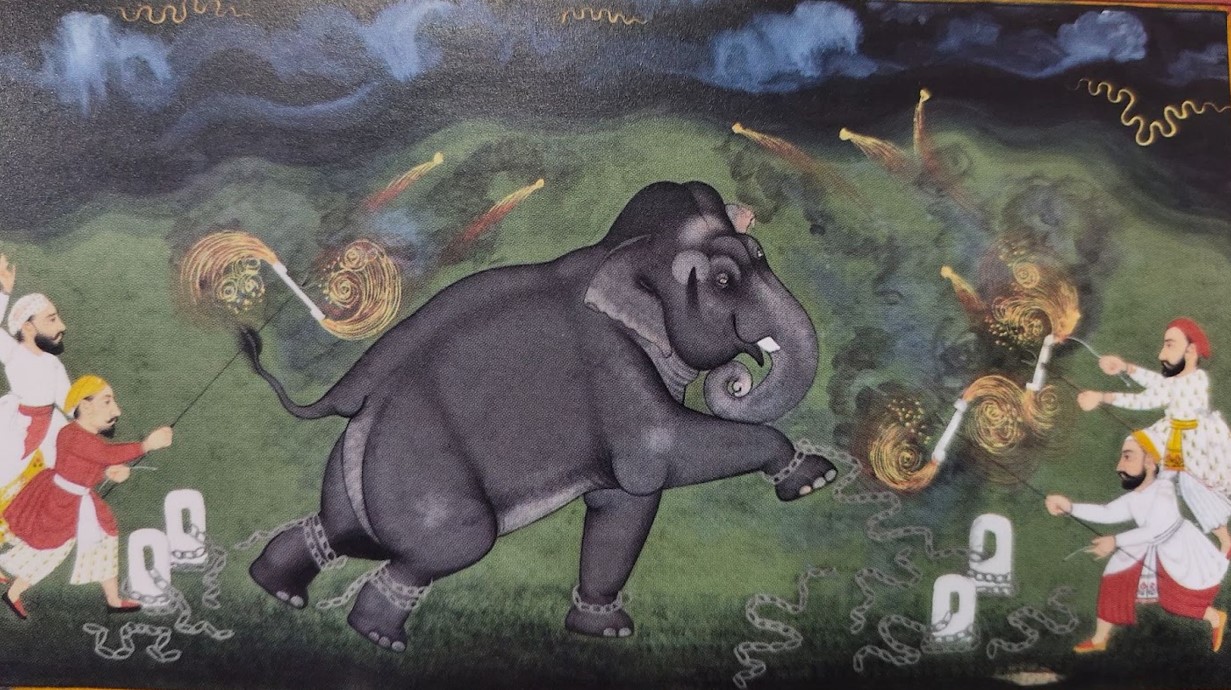

Medium used: Mewar paintings reached their peak around the 17th-18th century, which means that the raw materials that were used to create these paintings were organic elements. Natural dyes and pigments were utilised from sources such as vegetables, minerals, and semi-precious stones. Their canvas usually was made up of several layers of cloth stuck together and handmade paper. They would use brushes made from squirrel hair.

Style: These paintings have a background usually of earthen colours like red, saffron, and yellow with contrasting colour schemes used for the other elements in the painting. The sharp features of the characters in these miniatures make these distinguishable from the other Rajasthani miniatures. The figures have oval-shaped faces or are sometimes round with sharp noses & almond-shaped eyes. The figures of women are drawn shorter than the men. The clothes that the characters adorn are given a lot of importance, and the fabric draped around them is depicted to be transparent with light floral prints on their Chunnis, Ghaghra, and blouses. These miniatures usually have a bold border painted in mostly hues of red and yellow with sometimes floral motifs.

Process: Just as most miniature paintings were created around this era, Mewar miniatures too were created using handmade paper wasli. These papers were first cut to the desired size and then stuck one on top of another creating a layer. This was done to thicken the base for these paintings. Usually, as a restorative measure, a few layers of fabric were added to these stacks of papers. Around three to five layers were created using this technique. After this step was completed, the next step was to prepare the natural dyes and pigments, which were usually obtained by grinding the materials to a fine powder. These pigmented powders were then mixed with water and painted on the previously created canvas with the help of a natural brush which was usually made out of squirrel or camel hair.

Change in the art over time: Mewar miniature paintings were prominent throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. As the art form grew and reached its zenith, portraitures soon became a part of the theme that followed. However, religious-themed paintings remained to be popular and in demand.

New Outlook

The British's growing political power in the Mewar area during the 19th century did not affect the Mewar school's artistic legacy. The rules established a century ago were still followed in paintings. The second half of the 19th century has just seen a brief artistic change carried on by the visits of British artists including William Carpenter, Val Prinsep, and Marianne North. But by this time, Udaipur's manuscript painting tradition had significantly diminished, and photography eventually replaced the tradition of court paintings.

Books

- Pande, A. (2020) The Ragachitras of MewarL Indian Musical Modes in Rajasthani Miniature Painting. New Delhi: Aryan Books International.