Your Cart

Mata ni Pachedi

Let's learn about the Mata Pachedi paintings!

Introduction

Etymology:'Mata ni Pachedi' translates to behind the mother goddess.

Origin: This textile-based art form originated in Gujarat. Due to its similarity in tools and techniques of drawing, it is also called the Kalamkari of Gujarat. The tradition of painting the Mata ni Pachedis was started by the Vaghari community.

Location: The Vaghari community were nomads who moved along the coast of the Sabarmati River. Consequently, the exact location of their origin is hard to decipher. Today, however, the majority of the Chitaras or artisans have settled in Vasana, Ahmedabad, in Gujarat.

Community: The nomadic Vaghari community eventually settled along the banks of the river Sabarmati. They took up farming and agriculture as their livelihood.

Relevance: Mata ni Pachedi fulfills the need for a shrine or temple for communities that have no permanent settlement and thus need to construct temporary shrines for their religious ceremonies.

History

Historical Background: Mata ni Pachedi is a 400-year-old art tradition that originated as a form of religious expression in Gujarat, where it is still practised by several rural communities. This art is essentially an elaborate hand-painting on a fabric base which is hung during Chaitra Navratri, nine nights falling in March-April, and Sharad Navratri, nine nights falling in September-November, as a temporary shrine.

Culture and Societies: The Vaghari community was not allowed to enter temples. So, as a way to raise their voice against caste discrimination and also to worship the deity, they created Mata ni Pachedi, the textile-based art of Gujarat. As they were not permitted to worship the goddess inside the temple, they used to hang the piece of cloth where Mata ni Pachedi is drawn behind the temple. These textiles are heirlooms, and for constructing this shrine, multiple pieces of cloth are sewn together. The men of the community practice this art form, whereas the women tend to play little to no part in this. The Chitara community has been practising this art form for decades.

Religious Significance: These hand-painted fabrics are believed to have animal and human representations. Mata ni Pachedi was created to appease their 'Kuldevi' at the Maa Setrojia temple. It is believed that as the paintings are being made, anyone could touch or handle them, but as soon as it reaches completion, only the high priests can access them. When it's time to replace the old Mata ni Pachedi with a new one, the old textile is submerged and set afloat in a holy river.

Understanding the art

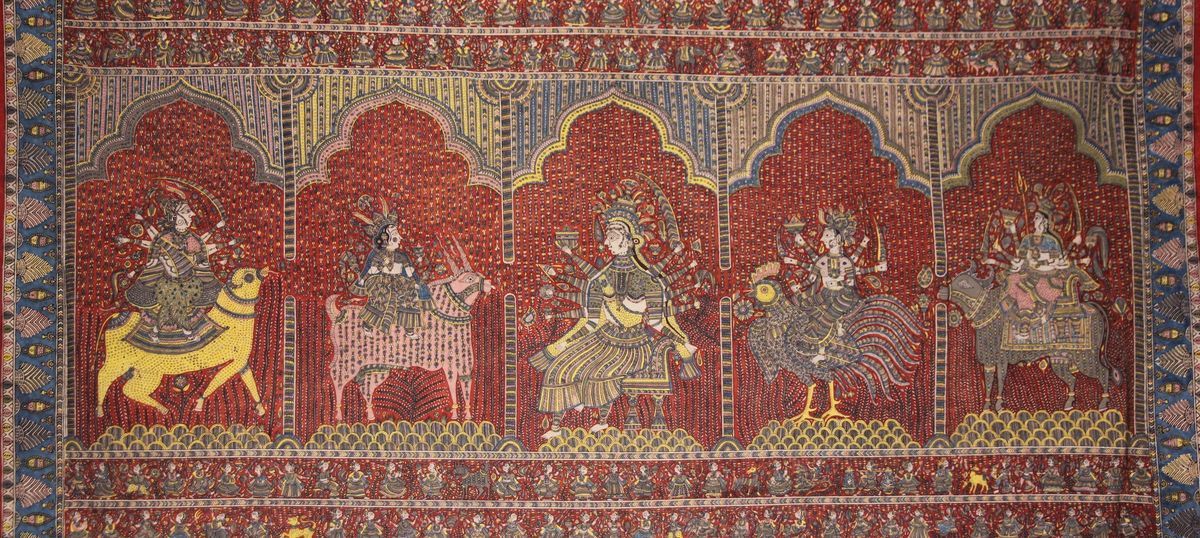

Central Motifs and their Significance: The central figure of these works contains a portrayal of one of the Hindu mother Goddesses situated in a temple or similar enclosure. Single God and Goddess in Hinduism are usually accompanied by a vahana or vehicle drawn on the fabric. Each panel of the fabric depicts a story about the deity. The animals shown in these textiles are dogs, roosters, goats, camels, and buffaloes. Besides these, other images in Mata ni Pachedi include instrument players, Hindu deities, firewood gatherers, astrologers, priests, and more.

Medium Used: Cotton cloth is used as the canvas of this art form. Natural pigments are used to paint. These tints are extracted from natural elements such as iron rust, tamarind seeds, jaggery, indigo, and henna. The tools used to create this art form are usually bamboo sticks and twigs that are dipped in ink to trace an outline before the colours are filled in.

Style: The main deity is drawn as the central motif with the most vibrant colours and is depicted to be clad in embellishments. The facial features are simplistic yet powerful. The remaining half of the textile is filled with human and animal figures. The human characters represent the devotees of 'Maata', and the animals are added as decorative features with a few floral prints. The borders are usually painted boldly and often adorned with painted carnations.

Process: Creating these decorative textiles is a tedious task. The fabric goes through various stages of treatment before the motifs are painted onto them. To start the process off, the cloth is soaked in water for a day to rid it of starch and is then sun-dried. The sun-dried and treated cloth is then soaked in a solution of a local chemical called 'harda', after which it is left again in the sun to dry. This process of creating the canvas takes two full days. Once the base is ready, an outline of the main sketch is prepared.

This artwork purely utilizes natural pigments, which are made from preparing and mixing dyes. Once the colours are applied to the fabric, it is washed off in running water to get rid of any extra pigment. The textile is then boiled in water with a mixture of the Dhawda flower and alizarin. This fixates the colours and aids in achieving vibrancy. Once the fabric is boiled for a while, it is then once again dried under the sun.

New Outlook

Wooden and mud blocks started being used as a method of saving time and producing products at a mass scale. Although these new kinds of blocks have been introduced, the use of natural dyes is still continuing. Another change that this art form witnessed has to be that this art form did not stay gatekept. It was opened up to a wider audience. With this change, an array of objects became canvases for these prints, such as saris, dupattas, bedsheets, and wall paintings. The material of fabric also changed, from using strictly cotton cloth to now a blend of silk-cotton is used.

Books

Fischer, E. (2014) Temple Tents for Goddesses in Gujarat India. India: Niyogi Books.

Fee, S. (2020) Cloth that Changed the World The Art and Fashion of Indian Chintz. United Kingdom: Yale University Press.

Erikson, J. (1968) Mata Ni Pachedi A Book on the Temple Cloth of the Mother Goddess. India: National Institute of Design.